Virunga Under Oil Threat – DR Congo

Ever heard of Virunga? It’s Africa’s oldest national park, and a treasured World Heritage Site, located in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and it could be threatened by oil exploration, writes Des Langkilde.

Rainforests, volcanoes, rare and beautiful wildlife – Virunga has it all. People who live and work there know it’s a very special place.

But Virunga is at risk of becoming Africa’s newest oil field. When the World Wildlife Fund (WWF®) heard that UK oil company Soco might explore for oil inside Virunga, they had to draw the line. Some places are just too precious to exploit.

Which is why the WWF are appealing to like minded conservationists to support Virunga by adding their names to a petition – every name helps to show governments and businesses how strongly people feel about protecting precious places like Virunga.

[box type=”info” align=”aligncenter” width=”5″ ]Join 294,212* concerned people and ‘Draw the Line’ by joining the WWF petition. (* The tally after the authors name was entered on 26 September 2013). To sign up go to: http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/where_we_work/congo_basin_forests/problems/oil_extraction/draw_the_line/?[/box]

Virunga National Park is the size of a small country, straddling the equator in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

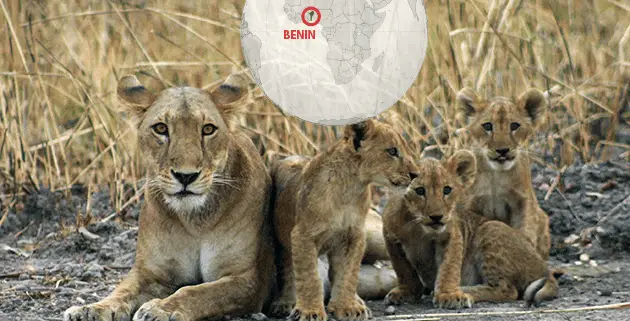

It’s got more than its share of wonderful wildlife – not just huge numbers of unique birds, but African icons like lions, elephants, hippos, chimps and the remarkable okapi. And some very, very rare gorillas.

Soco’s plan to explore for oil isn’t the only threat to Virunga – civil unrest and wars have put pressure on local people, wildlife and resources on-and-off for years. But we believe oil exploration would bring a new and unacceptable level of risk for Virunga’s environment and communities. Some people say local communities in Virunga will benefit from oil exploitation. But the WWF think it’s unlikely.

From the initial aerial surveys, to road-building, pipeline-laying, and of course the potential oil spills and pollution of land and water. (Lake Edward, in Virunga’s internationally important wetlands, is crucial for local livelihoods and food.)

WWF also contend that there are much safer, more sustainable, financially viable alternatives – including potentially lucrative eco-tourism and hydropower.

Valuing Virunga

Toby Roxburgh, Economics Advisor, WWF-UK, examines how we assign value to extraordinary natural places like Virunga National Park.

“Our insatiable demand for oil is leading to exploration in places that were once considered ‘off-limits’ – some of the world’s most special, important and fragile places – places like the Arctic and indeed, Virunga National Park in Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Virunga is a jewel in the crown of Africa’s natural heritage. It is Africa’s oldest national park, a World Heritage Site and a Ramsar wetland of international importance. It has a wide variety of habitats: forests, savannas, rivers, lakes, marshlands, active volcanoes and permanent glaciers. It hosts more species of mammals, reptiles and birds than any other protected area in Africa. It is home to about 25 per cent of the world’s 880 remaining critically endangered mountain gorillas.

The park also is incredibly important economically and socially, providing food and raw materials, opportunities for tourism and recreation, secure supplies of water for drinking and hydropower, and carbon sequestration, for example. Should oil exploration lead to extraction in or around the park, the consequences could be disastrous, and could undermine future economic development and the well-being of communities. It is not a development pathway WWF wants to see.

Our new report explores the potential economic value of Virunga under an alternative scenario – one of sustainable management and improved regional governance – to help highlight what is being put at risk.

Total economic value

The report takes a Total Economic Value approach, which recognizes the wide range of ways in which the natural world provides benefits to people, and distinguishes between so-called “use-values” and “non-use values”.

Use values are derived from nature where it contributes to human production or consumption, either directly (e.g. the provision of food, materials, etc) or indirectly through the function of various ecosystem services (e.g. the prevention of erosion by runoff or the regulation of climate by forests).

However, nature does not have to be used to be valued by humans. Many people value aspects of the environment even though they may never use or see them themselves, and hence they play no role in supporting economic production or consumption. These values are often called “non-use values”.

Non-use what?

Non-use values may seem abstract and intangible, but few would argue about their existence. They are driven by a range of motivations. For example, some people derive a value from merely knowing that the environmental “resource” – like a rare type of antelope or mountain gorilla–still exists, although they have no intention of using it (so called “existence value”). Some may derive a value from the continued existence of the resource – like a spectacular landscape or natural park – in case they may wish to use it in the future (so called “option value”). Part of the motive can also be related to the desire to preserve the resource – such as a healthy environment or a culturally or spiritually important site – for future generations (known as “bequest value”).

Non-use values tend to be more significant for important, unique, rare, iconic natural resources – for example like those in Virunga. Non-use values are a key reason why people donate money or sign campaigns to save endangered species such as giant pandas, tigers and whales from extinction, even though they are likely to never see them or derive any obvious benefit from their survival.

Non-use values could have important policy implications for Virunga. If even a small fraction of the global non-use value for the park and its resources could be captured and converted into revenue, it could provide a significant added incentive for safeguarding the park, for the DRC government and local residents.

Establishing policies and mechanisms to enable DRC to “unlock” the value of the park in a sustainable way is a monumental challenge, but we believe it is the best path”.

“That’s why we’re inviting you to sign our pledge to save Virunga, and to share it with your friends and family so that they too can learn about the amazing park we are fighting to protect” concludes Roxburgh.

For more information, visit: http://wwf.panda.org

About the WWF®

WWF® came into existence on 29 April 1961, when a small group of passionate and committed individuals signed a declaration that came to be known as the Morges Manifesto. This apparently simple act laid the foundations for one what has grown into the world’s largest independent conservation organization.

More then 50 years on, the black and white panda is a well known household symbol in many countries. And the organization itself has won the backing of more than 5 million people throughout the world, and can count the actions taken by people in support of its efforts into the billions. Having invested well over US$1 billion in more than 12,000 conservation initiatives since 1985 alone, WWF is continually working to bring a balance between the demands on our world, and the variety of life that lives alongside us.